Blog #7: Egyptian symbolism in the Milky Way?

1. We are interested in the spiritual aspects of ancient wisdom in our book. In this blog we explore the possible symbolism found in the stars by the Ancient Egyptians that relates to our personal development and awakening of higher consciousness.

2. In our last blog, “The Constellation Geb, the Egyptian Cygnus”, we considered that the layout of the Ancient Egyptian constructions on the Giza Plateau are laid out to possibly reflect both the constellations Orion, representing Osiris, and the constellation Cygnus, representing the neter of the earth Geb.

Figure 1A. Map of the pyramids with an overlay of the stars of the constellation Cygnus/Geb.

Figure 1B. Star chart of the constellation Cygnus/Geb.

Figure 1C. Image of the neter Geb.

Figure 2. Modern day image of the Milky Way with the constellation Cygnus/Geb on the right just above the horizon (http://www.dailygalaxy.com/.a/6a00d8341bf7f753ef01a3fd401485970b-pi).

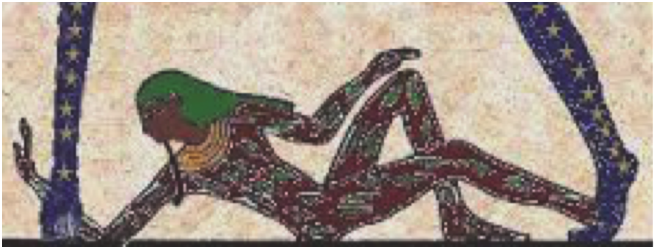

4. Nut and Geb are often shown in images with Nut filled with stars stretched above a reclining Geb.

Figure 3A. Typical representation of the reclining neter Geb under the neter Nut full of stars stretched above.

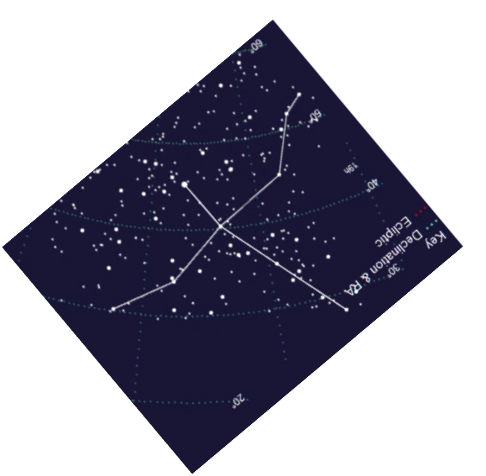

Figure 3B. A star chart showing the co-location of the constellation and the Milky Way which runs from the top left to the bottom right of the image.

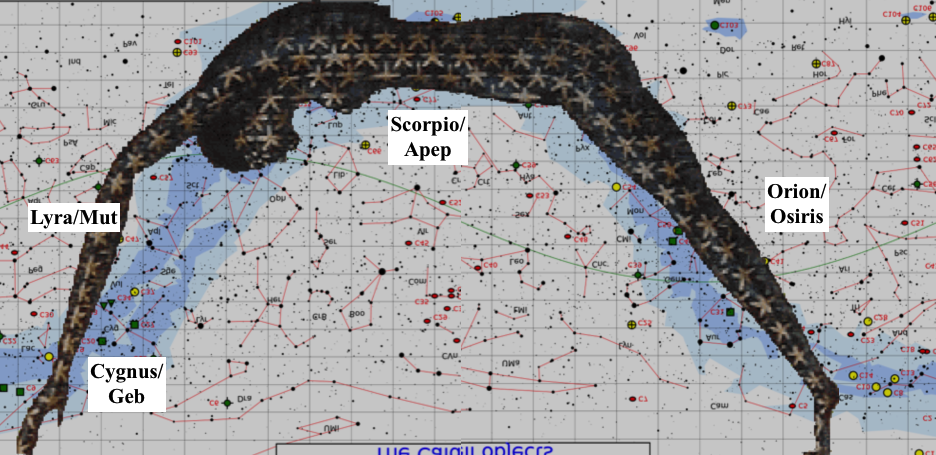

5. In our last blog we recognized the findings of Schwaller de Lubicz, Naydler and Sullivan that symbology often explores relationships through the juxtaposition of multiple images. In this case we look at the possible symobology where Cygnus, The Milky Way and Orion can represent Geb, Nut and Osiris.

6. In this case, on one side of the night sky we see Cygnus representing Geb the original creation of the world. Geb is sometimes represented as the goose that lays the World egg. Geb is shown in Figure 3A as lying under Nut, represented by the Milky Way. On the opposite side of sky we have represented for us Osiris as the constellation Orion slightly separated from the Milky Way in his re-membered and risen form following his journey through the Duat/Milky Way.

Figure 4. The Milky Way represented as a straight-line feature through the middle of a sky map showing constellations of interest to a journey through the Duat starting with Geb on the left and exiting as a resurrected Osiris on the right just below the Milky Way (http://www.atlasoftheuniverse.com/galchart.html).

7. The Milky Way can also be represented as a curved region through the sky as in Figure 5. In the figure we overlay a picture of Nut over a star chart of the Milky Way.

Figure 5. The sky-goddess Nut covered in stars as the Milky Way. Cygnus/Geb is aligned below her head on the left and Orion at the birth point on the right. We include a number of other symbols associated with the Egyptian myths including the important vulture neter of mother earth, Mut, Scorpio as the snake neter Apep involved in challenging the soul in the Duat. In this orientation Orion lies just above the Milky Way on the right. Nut image from http://www.egyptartsite.com/photo/nut.gif, Milky Way image is modified from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caldwell_catalogue.

8. The symbolism of these images is made explicitly active and representing a process is seen in the Egyptian image of the sun being swallowed by Nut at sunset and being regenerated as it is passed through her body before being re-born at dawn the next morning.

Figure 6. Nut swallowing the sun on the left and delivering a rejuvenated sun on the right (http://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/nut.html).

9. In this representation it is particularly interesting to note that the sun can’t be interpreted literally because it does not “travel the Milky Way” when it sets. It follows a different path called the ecliptic. The process represented in the picture must be seen symbolically.

10. While we are in no way experts in archeoastronomy, it is intriguing to consider the symbolism in the sky as it connects to our inner search for our higher Self. Finding this pattern in the sky captures the general theme of our internal development and connects with our experience of an inner creation. On one side of the night sky we see the original creation of the world represented by the laying of the World egg by the constellation Geb on the Milky Way. On the opposite side of sky we have represented for us Osiris as the constellation Orion slightly separated from the Milky Way in his re-membered and risen form following his journey through the Duat/Milky Way. Little and Collins (2014) explore similar passage through the Milky Way in North American myths. Earlier Sullivan (1996, page 341) wondered ‘It may be coincidence that in Andean cosmology (and archaic cosmologies world-wide), the dead “return” through the bridge at Scorpius, the center of the galaxy, while the immortals, like Buddhists escaping the “wheel of karma” “leave” this mortal “coil” via the shortest route – beyond Gemini – to the highest heaven, beyond our galaxy.’

11. These views of the sky, as we interpret them, provide a potential symbolism of Geb, the Milky Way and Osiris as a symbol for the way of awakening consciousness as we live our lives today. With proper understanding, these ideas could be a most useful map of our own personal development: beginning with the original creation of consciousness followed by a challenging passageway that potentially leads to our resurrected re-enlivened Self.

13. The search is not in the stars or on the face of the earth, but in ourselves.

BUY NOW: https://www.amazon.com/Awakening-Higher-Consciousness-Guidance-Ancient/dp/1620553945/

References:

Gregory, L., A. Collins. 2014. Path of Souls: The Native American Death Journey: Cygnus, Orion, the Milky Way, Giant Skeletons in Mounds, & the Smithsonian. ATA-Archetype Books.

Schwaller de Lubicz, R.A. 1998. Temple of Man. Inner Traditions.